The Current Conservation Status of Horticultural Genetic Resources and their Cryopreservation Future in Syria

Shaher Abdullateef, Ina Pinker and Michael Böhme

Department of Horticultural Plant Systems

Faculty of Agriculture and Horticulture

Humboldt-Universitaet zu Berlin

Keywords: plant genetic resources, in situ, ex situ, genebanks, biotechnology

Abstract

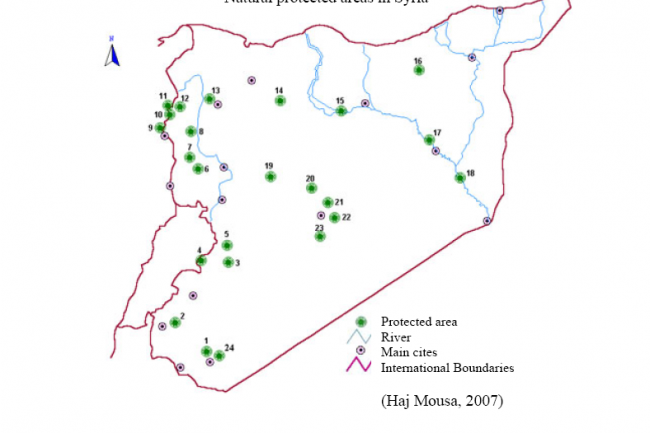

Syria, located at the eastern side of the Mediterranean Sea, has a unique potential and richness in genetic diversity. There are over 3150 plant species among them world-wide important plants, e.g. almond, apple, date palm, pear, pistachio, and olive. Because of numerous man-made and natural pressures, losses in biological diversity especially for apples and wild olive are recorded. Therefore, in collaboration with IPGRI and FAO, a national program for plant genetic resources conservation was established 10 years ago. It involves in situ, ex situ and in vitro conservation approaches. In the frame of this program, characterization of the genetic diversity of local Syrian cultivars has started. The in situ conservation of wild plant species is carried out through over 22 protected areas and 2 national parks of 315,221 ha in total. Ex situ conservation includes seed genebanks to storage seeds for long-term (at -18°C to – 22°C) and medium-term (at 0°C to 4°C), field genebanks to storage apple, pistachio, wild olive etc., and botanical gardens. In vitro conservation is used to maintain local cultivars of potato. For vegetative propagated plants, cryopreservation could be a promising technique for long-term conservation. However, in spite of availability of cryopreservation protocols, this technique is not used in Syria due to a lack of coordinated research, as well as limitations in efficient and robust cryopreservation protocols and technologies.